By Jeanne Century

The field of education improvement defines what it means to scale an innovation in many different ways. Cynthia Coburn (2013) provides some guidance in her seminal article that suggests there are four elements of the end state of being successfully “at scale.” These include depth, spread, sustainability, and ownership. Each of these elements has its own challenges for measurement and research. In this blog, I am going to focus on what I think is the simplest of the four — spread. Simply put, spread is the movement of an innovation to “greater numbers of classrooms and schools.” (Coburn, p. 7).

Before we can meaningfully talk about ways to measure and research spread, we have to be clear about what we are spreading. In education, improvement efforts often entail a program, intervention, or innovation of some kind. I typically use the word “innovation” to refer to all of these, particularly when it comes to spread. My reasoning is that even if an innovation has been around for a long time, if it is new to the target participants or users, it is an innovation to them, and we should recognize it as such.

Spread in Action: With support from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, a number of research-practice partnerships (RPPs) set out to “scale” innovations in school districts. While they may have defined “scale” in different ways, they all aimed to spread their innovation. The innovations ranged from specific instructional materials, to approaches such as Problem-based Learning (PBL), to individual instructional strategies (e.g., facilitating student argumentation).

Let’s put the individual instructional strategies aside for a moment. In typical discussions of spread, instructional materials, PBL, and other multifaceted innovations are often thought of as a “whole.” Meaning, practitioners and researchers ask if the innovation (as a whole) has spread; where the innovation has spread; and what factors have contributed to or inhibited the (whole) innovation to spread. We might hear statements like, “an innovation has “spread” to 25% of the schools in the district or 75% of classrooms.” But, what do these spread metrics really represent? We need to take a closer look.

It is widely recognized among those working to spread innovations, that complex innovations never spread as is. In education, we know that teachers adapt innovations for a variety of reasons. When teachers make what some call “principled” adaptations to account for local contexts and conditions, outcomes may improve. In contrast, when teachers make reactive, ad hoc adaptations in response to time shortages or pressures to focus on something else, “fatal” adaptations may occur, leading to poorer outcomes.

I suggest that the field might consider “Component-based Research” (CBR) as a way to better understand these issues. CBR calls for practitioners and researchers to look at innovations as being composed of smaller elements, or “components.” Doing so enables researchers to collect specific information about innovation spread and more thoughtfully account for, and interpret, other data and findings that influence outcomes.

When it comes to spread, it is quite unlikely that all of an innovation’s components (as a whole) are actually spreading. A more actionable way to tackle understanding spread is to recognize that components of the innovation are spreading, alone or in combination with others. Focusing on components, rather than the innovation as a whole is a better unit of analysis for measuring spread and interpreting analyses related to spread.

Now let’s return to the Hewlett grantees focused on spreading individual instructional strategies. In these cases, the improvement teams aren’t focused on multi-faceted innovations with many different components. Rather, they are focused on “innovations” that are already at a component “grain size.” For example, many “whole” innovations (like instructional materials units) might include the teaching practice: “teacher facilitation of students engaging in argumentation.” In this context, facilitating argumentation is a component of the whole intervention. In our (Outlier) RPP with Broward County Public Schools however, this teaching practice is the innovation we aim to spread (as well as two other specific practices). Our innovation is already at what we would describe as the component level.

Some of you may recognize CBR as resonating with implementation research. Indeed, implementation research is one type of CBR. Typically, implementation research aims to measure innovation implementation, sometimes at the component level, at a particular time and place to inform continuous improvement, and/or to help explain the “why” and “how” behind particular findings. CBR, on the other hand, has a broader vision to use the specification of innovation components and other variables (e.g., influential factors, beneficiary characteristics) to look beyond single innovations or instances of an innovation to accumulate knowledge across many, widely varied innovations that share common components.

Using a component approach will enable the field to grasp spread as more than an account of whether an innovation is “in” a classroom or school at a particular time. Rather, it illuminates the dynamic processes of spread and helps to build understandings about the contexts and conditions that do and do not support the spread of particular innovation components. It also enables practitioners and researchers to look at relationships between particular innovation components and student outcomes, paving the way for innovation creation and improvement using local customization. Finally, because components exist in many different innovations, CBR enables us to accumulate knowledge in a way that focusing on whole interventions does not.

It is time we embrace the complexity of spreading improvement to bring the most promising versions of an innovation to each district’s schools and classrooms. Rather than ask if an innovation spread, we need to ask “what parts” of the innovation spread? We can then ask, “Why did this component spread in these locations?”; “Why did this component fail to spread at all?”; “Why do these components seem to happen more in these contexts?”; and Why does this component seem to be associated with this particular outcome for particular groups of students? Eventually, we may be able to ask, “What parts of this innovation should spread, given our student population and district context?” When we treat innovations as “wholes,” we cannot collect and interpret data at the level of clarity and specificity we need to bring about customized, place-based improvements to education. Using a CBR orientation will move us closer to being able to do this, and in turn, move us closer to being able to bring more equitable opportunities to our learning settings.

Coburn, C. (2003). Rethinking scale: Moving beyond numbers to deep and lasting change. Educational Researcher 32(6), 3-12. https://www.sesp.northwestern.edu/docs/publications/139042460457c9a8422623f.pdf

For more information on implementation research and component approaches, see: Advancing the Use of Core Components of Effective Programs and Implementation Research: Finding Common Ground on What, How, Why, Where and Who

Guest Author: Kaitlyn A. Ferris

In today’s technologically-advanced society, it is hard to imagine virtual learning being unsuccessful or the reasons why public schools are struggling to provide students with high-quality virtual learning experiences. After all, many adults are dependent on their phones for survival and children are becoming technologically literate at earlier and earlier ages. Even though these may be true, the COVID-19 global pandemic has made it clear that not all students have equal access to supportive learning environments and the resources to support virtual learning. Inequities in these areas make it challenging for young learners to thrive and develop skills to help them succeed in the virtual classroom.

Imagine the following…

It’s early Monday morning. Another week of school is just beginning for you and your 4th-grade classmates. This week, like many school weeks since late March, is now conducted virtually. You will be participating in e-learning with your teacher and fellow classmates this morning. As you brush your teeth, pick out your school outfit, and grab your backpack filled with school supplies, your Mom yells to you and your younger siblings, “Hurry up, I am late for work!” Your Mom works cleaning houses across town, and her work schedule has not changed despite the global pandemic. She cannot leave you at home to babysit your younger siblings, you’re only in 4th grade after all. Even if you could juggle your role as a student and caretaker for your younger siblings, your house does not have reliable internet access leaving you unable to join your class’ morning Zoom session if you stayed behind. Instead, you pile into the car with your Mom and siblings and drive across town. Your Mom will be busy all day, and you cannot bother her while she is working. Plus, you remember that your teacher will be starting the morning Zoom session shortly. She’ll wonder why you are absent if you don’t log-on and probably call your Mom to ask why, which will only make your Mom more stressed out. Luckily, the house where your Mom works has really strong, reliable internet access so you don’t even need to leave the car to join your classmates on Zoom. You fire up your computer, connect to the Wi-Fi network that by chance does not require a password, and sign into Zoom. You see your classmates, joke about what you did over the weekend, and complain about how much time you spent doing homework all while your younger siblings giggle and squirm right next to you in the backseat of the car. Your internet connection is strong enough so you are able to make it through today’s math review lesson without any connectivity issues. Those two hours of virtual class time flew by. You sign-off Zoom just as the driver’s side door swings open and your Mom starts the engine. Your Mom puts the car in reverse and you speed away to her next job site. As your Mom pulls into the driveway at her next house, you think about starting your homework since this house does not have an Internet network that you can join and it’s only noon.

Now, close your eyes and envision what you just read.

Were you questioning how it was possible for this student to retain anything discussed during that morning’s Zoom session or how this student could have possibly participated in the lesson with younger siblings chatting and laughing nearby?

Are you struggling to believe this scenario is one many students are forced to navigate during the global pandemic?

Are you thinking that this example is fabricated?

Unfortunately, it’s not.

This situation and others like it are very real. Teachers across the country are signing into Zoom and observing their students learning everywhere and anywhere they can — in their Mothers’ cars or the Taco Bell parking lot — and in their living rooms using the one smart-device available for the whole family. The digital divide is widening at an alarming rate, and when we put a face to the statistics this is what it looks like when one student tries to navigate the challenges of virtual learning in the COVID-19 global pandemic.

By David Sherer

This fall, should students only be taught online? Or should they be physically present? Perhaps it’s best if they experience some type of “hybrid” classroom? If so, what ratio of in-person to digital instruction should they receive? Should students and parents get to choose their options? How about teachers?

Right now, districts across the country are agonizing over these questions. However, such decisions about which instructional model to choose may be less vital than we imagine. Here are two reasons why.

If you accept these points, then you might be thinking, “Well then what are school districts supposed to do?” Of course, it’s important that districts choose some type of instructional model based on their best interpretation of existing research, their own experiences, and opinions from the community. This choice will likely be constrained by what is politically feasible and/or operationally possible. However, I argue that making this choice is only the beginning.

Given the novelty of our current conditions, districts must also put in place systems to continuously learn about their instructional models, determine if they are having their intended effects, and adapt them for particular schools, classrooms, and students. But how should they do that?

Taken together, these elements of a learning system provide a means for districts to both execute their model well and improve it over time. Importantly, to use such a system, it’s vital for districts to approach their work with humility and a learning stance—where they are open to being wrong and interested in “learning as they go.”

Districts are trying to answer a lot of questions right now about their instructional plans. But, as they prepare to re-open, it’s important for them to realize that putting in place good systems for “learning as they go” may be more important than choosing the “right” model.

Felicia M. Sullivan

Since 2014, New Hampshire’s Performance Assessment for Competency-based Education (PACE) system grew the number of performance tasks in mathematics, English Language Arts (ELA) and science from 14 to 112, an 800% growth. In that same time period, PACE went from no performance tasks scoring on state mandated Work-Study Practices (WSPs) -- self-direction, collaboration, communication, and creativity -- to 51 tasks that included at least one WSP proficiency score. And in the 2018-2019 school year, the system developed 6 performance tasks that not only scored the WSP of self-direction, but embedded self-direction instruction along with content instruction.

As part of a William and Flora Hewlett Foundation funded research-practice partnership (RPP), JFF (Jobs for the Future) has been collecting data and insights on the scaling of WSPs (aka deeper learning competencies or essential skills) in New Hampshire. From the start, the state’s PACE system was a key driver to scale, providing a critical backbone for assessing competency-based efforts. What has become clearer to the JFF research team is that investing in teacher capacity to instruct and assess WSPs has been a critical move to ensure that the practice change is deep, spreads, and is sustainable. A key orientation has been a strong commitment to teacher ownership of the process. The practice partner is this effort, the New Hampshire Learning Initiative (NHLI), has been critical to supporting and pushing this teacher-centered approach forward.

Often scaling new teaching practice or education reform starts with bringing new practice to teachers. Teachers are trained with attention to fidelity in the implementation. They may also provide insights into what key design changes need adjustment to be truly classroom ready. These efforts may start with small pilots that expand outward or enter the system as a broad-based initiative. Rarer are the practice change initiatives that engage teachers in the design of the practice change effort or provide them with the skills and capacities to do so. For the WSP effort in New Hampshire, investments in teacher skill building in quality performance assessment, evidence collection, intervention improvement, and peer leadership have resulted in a cadre of teachers who are not only owning practice change in their classrooms but are championing and pushing for the work back in their schools and districts.

As Dees and Anderson (2004) noted, mitigating the barriers to scale start by assessing readiness, emphasizing the reward, minimizing risk, providing resources, working with those who are most receptive. In designing the professional learning opportunity for performance assessment of WSPs, NHLI attended to all of these important pre-scaling dynamics. Specifically, NHLI:

Lowering the barriers to scaling, doesn’t necessarily mean that scaling will occur. As with setting the stage for scaling, NHLI works to support the development of performance assessment for WSPs through a strong teacher-centered approach. In particular, identifying and supporting teacher leaders has been key. These leaders are identified primarily because they have demonstrated strong motivation and interest in bringing their own practice to a deeper level. Additionally, as they build their own core strengths and develop instructional strategies in their own classrooms, these leaders are open and willing to share with others both in and outside their districts.

In Cynthia Coburn’s Rethinking Scale (2003), the author articulated four key dimensions to scaling practice change in educational settings – depth of pedagogical change, spread, shift in ownership, and sustainability. In the WSP work in New Hampshire, here is how these features are playing out:

By putting teachers at the center of learning, development and diffusion to WSPs, NHLI as tapped into strong scaling motivations like problem-solving, autonomy, and problem-solving, all within a cooperative, peer learning community (MacLachlan, 2016). Replicating the large-scale mindset shift is no easy feat, but the keys and levers to success discussed here are a good guide to get started. If you’d like to find out more about the work on scaling deeper learning in New Hampshire, visit our project Building Essential Skills Today (BEST) for the Future on the web at http://www.best-future.org.

Special thanks to Ellen Hume-Howard, Paul Leather, Kathy White, Jonathan Vander Els, Ann Hadwen, and Mariane Gfroerer for their deep and reflective thinking about their work and efforts to scale and sustain deeper learning. And a shout out to the great teacher leaders and administrative leads who are the secret sauce to making it all a reality – Cathy Baylus, Angel Burke, Kathy Cotton, Tony Doucet, Elizabeth Gouzoules, Kelly Gray, Donna Harvey, Patricia Haynes, Brittany Lombardo, Chris Longo, Jessica Tremblay and Nicole Woulfe.

Felicia M. Sullivan, Ph.D. is an Associate Research Director at JFF (Jobs for the Future). Her research interests include human development and organizational learning towards system change as well as the effective translation of research and evidence through cross sector collaboration. She is currently researching deeper learning outcomes for middle and high school students and the diffusion of innovation and scaled impact. Email: fsullivan@jff.org Twitter: @feliciasullivan.

Guest Author: Annmargareth Marousky

Broward County Public Schools

This blog post highlights how three 5th grade teachers used the same writing lesson and “Silent Debate” to engage widely varied learners in deeper learning (e.g. argumentation, use of evidence to support claims, and communicating points of view). These lessons were done before COVID-19 the transition to virtual instruction. However, it is easy to imagine how some of their strategies can be applied to support deeper learning in a virtual instruction environment.

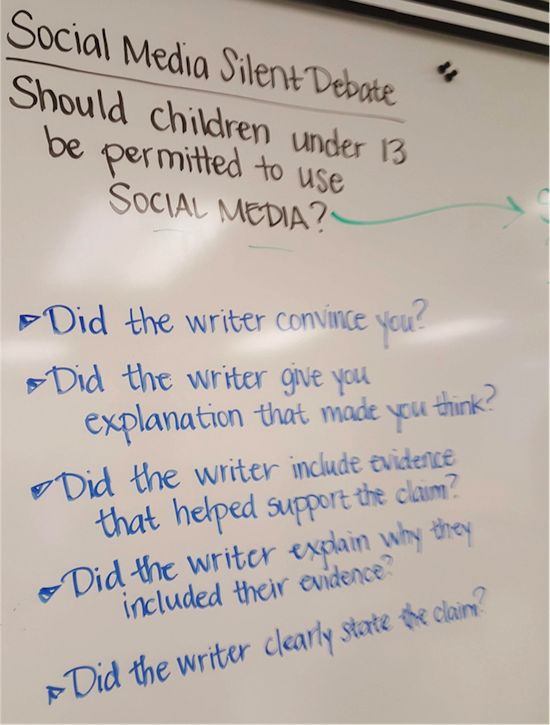

Over the course of several days, the 5th grade students in each class were given the prompt, “Should 13-year-old or under students be permitted to have social media accounts?” and asked to research, brainstorm, and write an opinion paper in response.

All students were given articles to read on the topic of social media for young students. After reading the articles, students brainstormed a list of social media platforms and the pros and cons for each. Based on their discussions and articles, each student decides on their stance on the question. Then, they engage in “Silent Debate” during which they read, present and support their points of view. In “Silent Debate,” teachers still expect full interaction, active participation and lively communication, but students may not speak; all communication is written. Using evidence to support their claims just as they would in an oral debate, students created an original post of their opinion and responded to posts of their peers. Ultimately, they were asked to write an opinion paper using the RACE writing strategy (RACE is an acronym for evidence-based writing. Students must R — restate the question; A—answer the question; C— cite evidence; and E— explain how the evidence supports the answer).

Each teacher modified the lesson to support deeper learning through collaborative argumentation and evidence gathering without sacrificing the needs of their class. Here are their stories.

About 65% of Mr. Balmori’s class is on free or reduced lunch and his students are a mix of ethnicities and ability levels including an autistic student with a full-time assistant. For this lesson, Mr. Balmori used an interactive white board to share directions, to brainstorm a list of social media platforms, and to generate a list of pros and cons. This enabled him to make sure every student had a constant reminder of expectations and to respond to questions for the whole group’s benefit.

Mr. Balmori used the Canvas platform to post the writing prompt and directions and students used it to post their responses. Only after students posted their own opinions, supported by two pieces of evidence, were they able to see and directly respond to their peers. They had to respond to three others including one who had a similar viewpoint (and provide them with more supporting evidence) and one that had an opposing viewpoint (and provide evidence against their viewpoint). For example, "Although you say that Social media can be dangerous because it can invite unwanted people into conversations, there are measures that can be taken to prevent this and keep the users safe." Finally, they had to write an essay supporting THE OPPOSITE stance that they originally took using each other’s discussion posts as the "sources" of support and referencing them throughout their essay. In the end, the class opinions were evenly split and yielded some intense, passionate debates including expressive and elaborate explanations of support.

Mr. Balmori’s reflections: “This design was the best fit for my students. It helped breach the anxiety that my class was feeling every time they were “forced” to write. Be it with typing or writing in their journals, my students said “writing” [is] a bad word. But this activity had many of them actively writing and enjoying their learning process.”

Ms. Paz’s class is a gifted/high achieving group. About half entered the program through “Plan B” which considers socio-economic status as well as intelligence. About 65% are on free or reduced lunch (FRL) and most are very tech-savvy and comfortable expressing themselves and their differing opinions.

Ms. Paz used a dry erase white board to document her students’ social media platform and their quick whole group discussion on the pros and cons of each. She decided to use Silent Debate to ensure that everyone's voice would be heard. Ms. Paz had a few students who would overpower the discussion so much that she had to intervene to ensure others could be heard. This format allowed the students who wouldn't ordinarily share to interact with multiple students and express themselves clearly. Others, who required more time to think about their responses, were able to do so; wait time is less of an issue with an online conversation. Ms. Paz asked her students to complete their assignment on paper but still had the students use each other as sources of evidence to support their opinion and were encouraged to use counterevidence if it was used appropriately to support their point.

Ms. Paz’s reflections: Ms. Paz felt that the lesson went well and especially liked that her quieter students stood out because they were not afraid to share in this format. Students replied to many other students – not only the required few. She was especially happy to hear some of her students say they didn’t feel strongly about either opinion, so they purposely chose the side that they felt others wouldn't choose because they wanted to get the biggest reaction.

Ms. Ayres’s class consists of 22 racially diverse students including 11 being progress monitored for Reading, 9 being progress monitored for Math, 3 receiving intervention services for behavior or academics, and five students with disabilities (speech, specific learning disabilities, and ADHD).

Ms. Ayres started her lesson with a group discussion on social media and immediately hands shot up into the air. This class loved to share and participate, especially about a topic they were interested in. She recorded their discussion on her white board. Next, she divided students into pairs to discuss their opinions to make the discussion more personal and easier to navigate; many students could easily go off topic or overpower the conversation. Teams, rather than groups, ensured that everyone could share their thoughts without fear of embarrassment.

During their discussion the students recorded their opinions in a positive / negative T-chart on a paper. Now, better prepared, students were asked to go to their laptops and post their responses on Canvas. Although it was difficult for the students not to talk, the Silent Debate allowed them to feel more confident about posting their thoughts without fear of judgement from others. It also gave those students who have difficulty formulating their position more time to gather their thoughts and benefit from the discussion they had with their partner. Some students even “talked out” with their partners what they might write before going to the laptop.

Ms. Ayers’ explained what happened next: “I asked them to pick a side for the prompt and tallied how many students thought one or the other. Most students picked that they should for the obvious reasons which I knew would happen. lol. They didn't know what trick I had up my sleeve! Afterwards, I explained that they would now begin writing their essays, but there was a catch! They had to write about the opposite of their opinion.”

Ms. Ayers’ reflections: “Overall, I thought this lesson was amazing because the students were extremely involved. They were discussing and sharing ideas. I also believe it made them think twice about their uses of social media and how they need to be careful.” Although they were not happy with her for the writing instructions, she choose this approach because her students needed to understand that they may not always have the choice to write about what they want to. She also felt it would make them better writers because they now had to think of the opposite side.

By Jon Norman and Kelly McMahon

Teachers are masters at solving dilemmas that surface when unexpected events derail their plans for teaching their students. Their classes may be interrupted by any myriad of things on a daily basis. From an unexpected fire drill or the copier breaking down during the only free minute a teacher had available to make handouts for her next science lesson, routinely, teachers must balance their planned activities for helping students learn content or develop new skills with unwelcome realities. The plans that they are actually able to deliver in the face of constant interruptions often differ from their aspirations. Yet, the current crisis caused by Covid-19 has created novel problems for educators as they are trying to create new ways to teach their students, collaborate with colleagues, and partner with families virtually – all the while trying to manage uncertainties in their own homes.

When teachers (or anyone, really), encounter a problem, they tend to look for a cause. If the cause of a problem is clear, they can identify a solution and take action. For example, if a teacher planned to have his students draw the plot line for Macbeth, but students don’t have pens or pencils, the solution is obvious: provide writing instruments in class. When the causes of problems are obvious, then teachers can identify a solution - even if it is a short-term solution - that allows all students to access valuable learning opportunities. But, the current conditions have created much more complicated problems. It is not easy to figure out what actions to take, or how to prioritize among options that could solve the problem that all teachers are currently facing as they try to figure out how to teach virtually so that all students experience meaningful learning today, next week and, maybe, the rest of the school year.

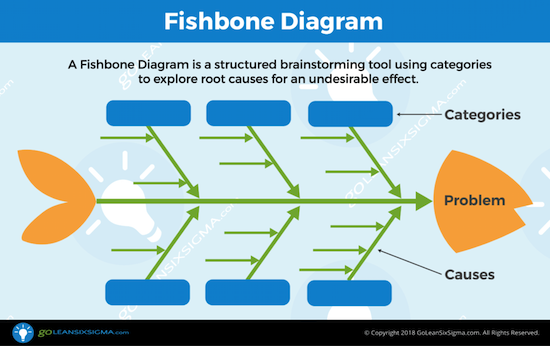

To attend to what might seem like a mountain of challenges needing immediate responses, we think improvement science could prove helpful. The principles of improvement science point to a set of tools, methods and a way of thinking that help with complex-problem solving. One key tenet of improvement work is to understand problems in a particular context so that we can identify that there are multiple causes contributing to any one problem and help us see that not all actions are equally helpful, if we want to solve a problem.

Once the things that are stymying success are identified, an improver can consider each one: is it something that she can change? Is it something that, if she changes it, will have a big impact on the overall system, or a small one? And is it something that is relatively easy or hard to change? An Improver strives to identify aspects of her context that are (1) within her power to do something about, (2) if shifted, are likely to help things a lot rather than a little, and (3) are manageable to accomplish. Doing so yields a twofold bonus: first, it gives the improver some sense of control in a swirling, dynamic system, and second, it also increases the likelihood that anything she changes that she thinks will be a solution in her context will actually improve things.

One of the first steps in trying to understand a problem in context is to make a list, diagram, or drawing of everything that’s causing the system not to work the way a teacher wants. For example, a teacher who has suddenly found herself emailing students assignments and then creating a digital space for students to turn them in may find herself with the following challenges:

A teacher or someone else working with students likely face many other issues – this is just meant as an illustrative snapshot. Now the teacher can take this list, and order things based on how big of an impact they have on her system. She might note that the fourth aspect she identified – that some students don’t have computers at home – would have a pretty big “bang for her buck,” if fixed for those few students, but may be outside of what she’s able to change, at least at this moment. Instead, she might consider that the second thing on the list – not having email addresses – represents a big challenge to students’ learning, since they don’t get learning materials, and also something she might be able to address herself. The teacher can decide which things are most influential in preventing her students from engaging in the learning activity, and then act on those that are both impactful and doable.

We present this idea of looking for solutions that teachers can tackle in an effort to help teachers understand the complex problems they face, the relationship between causes of these problems, and how to decide on what to address so that they can focus on providing meaningful learning opportunities for all of their students. This isn’t a panacea for all the issues educational systems are confronted with at the moment. But it is one way of approaching how to change something that isn’t working in real time, and it’s change that comes from the people doing the work themselves. And during this time of vast uncertainty that demands adapting under pressure, we offer this as one lesson from improvement science that could help educators meet their aspirations for teaching all of their students well - as we know teachers are prone to work furiously to do - no matter the size of the disruption.

Written by Erin Henrick and Don Peurach

Special thanks to thought partners Paul Cobb, Caitlin Farrell, Laura Wentworth, Paula Arce-Trigatti and participants in the 2020 Workshop of the Improvement Scholars Network

The rhythms of all our lives have been severely disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. These disruptions are particularly acute in America’s public schools. Routines and ways of learning that have carried students, teachers, and educational leaders for decades – if not centuries – have been interrupted. Millions of students who would otherwise be in classrooms, on playgrounds, and on athletic fields are sheltering in place at home with their families, with millions of teachers and educational leaders working steadfastly to maintain some level of educational continuity via online learning. Many know already that they will not be returning to school this year, and others are left to wonder.

While we lack a clear vision of what the future will bring, we can anticipate some of the ramifications of extended school closures that will challenge educators moving forward. For example, in the upcoming 2020/2021 school year, schools will be called upon to address student trauma from the effects of COVID-19 on families and communities, stemming from issues such as isolation, sickness, hunger, abuse, and economic hardship. In addition, schools will face the challenge of assessing student learning and determining the best way to address gaps in learning that will certainly be exacerbated by extended periods of remote learning or no school at all.

Compounding these issues, experience and research have shown that these matters will prove more complicated for traditionally underserved students, including students of poverty, students of color, students with disabilities, and English Language Learners (ELL). While some districts and schools will be well positioned to deal with these challenges, many will not. All states and districts will be working against resource constraints arising from new economic hardships amid the usual turbulence that marks the beginning of the school year (e.g., student, teacher, and leader transiency) and amid the very real possibility of the re-emergence of COVID-19 and the need to resume social distancing.

Now is a challenging time for educational researchers who want to help. But wandering into complex, uncertain, and unprecedented conditions likely to be playing out in districts, schools, and classrooms without considering the tremendous strain under which educators are currently working might do more harm than good.

That, in turn, leads us to the purpose of this blog -- to consider the question, What is the role of education Research Practice Partnerships amid the COVID-19 pandemic?

RPPs are specifically designed to address problems of practice that affect educators. To be clear, schools and districts face challenges today vastly different from those they faced just a few weeks ago. Indeed, this moment presents possibly the most radical shift in problems of practice that educators will encounter in our lifetime, if not in the history of US public education: rapid movement to online learning, rapid professional development for teachers on how to use online learning and telecommunications platforms, and enormous equity issues related to educational access and quality. Moreover, districts differ considerably in their responses, as some central offices and schools are well positioned to support schools and teachers making these shifts, while many others are not.

Though now is probably not the right time to start a new partnership, established partnerships may well adapt and adjust their joint work to address current problems of practice faced by districts and schools.

In our view, researchers actively engaged in mature RPPs (or other collaborative research improvement efforts) may be positively positioned to contribute to these efforts. Because researchers working in RPPs typically spend time and energy developing relationships and connections, mutual trust and “ways of working together” that have already been established may support shifting research plans and study designs to address new challenges. Yet, even then, whether an RPP is well positioned to help during this time depends largely on the types of expertise present within the partnership.

We encourage partners to meet and discuss the question, How can our RPP respond in a way that is useful and relevant given the unprecedented challenges facing our practice partners?

Because of the nature and scope of the partnership, the answer may be to temporarily pause work. However, another answer may be to propose new work or adapt current work to address the urgent challenges that have emerged due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Here are some potential ideas for ways educators working in RPPs might be able to help. Specifically, RPPs may be positioned to support the following:

Researchers and their practice partners can come together to determine how to best shift/adjust/pause joint work in this challenging time. Still, researchers in RPPs should proceed cautiously and take care to privilege the priorities and work of their practice partners over all else. School and district leaders are in uncharted territory right now, so partnership work ought not to impose added demands on practice partners. Without a doubt COVID-19 has dramatically changed the landscape of education. Now more than ever, education researchers should aim to be sensitive to the needs of practice partners when working to understand and address the complex challenges sure to follow.

______________

Erin Henrick is an education researcher, evaluator, and professional development provider, specializing in Research Practice Partnerships. Dr. Henrick is President of Partner to Improve, an education research and consulting group supporting improvement and systemic change in education through powerful partnerships. Dr. Henrick is also an instructor in the Vanderbilt Ed.D. program in Leadership and Learning in Organizations. She co-authored the book Systems for Instructional Improvement- Creating Coherence from the Classroom to the District Office.

Donald J. Peurach is an Associate Professor of Educational Policy, Leadership, and Innovation in the University of Michigan’s School of Education. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Peurach’s research, teaching, and outreach focus on the organization and management of instruction in education systems, with a particular focus on network-based continuous improvement.

Destiny Warrior

OKC EQUIP: (Equity, Unity, Intentional, Participation): Generation Citizen’s partnership with OKCPS extends beyond our curriculum and professional development. It is a partnership, driven by data, that will identify the equipment students need and best practices around how educators deliver it.

Collaboration brought OKC Equip and DIG Deeper together beyond our Research Practice Partnership (RPP) cohort. The work of the Dig Deeper RPP resonates with the work we are doing to scale deeper learning across a diverse district. We are striving for sustained impact in the classroom and across the district while providing the clarity that can restore the agency and academic optimism of students and educators in the district’s highest-need schools.

Through professional learning workshops, OKC Equip invites teachers to explore specific Collaborative Project Based Learning (CPBL) pedagogies: elevating student voice, emphasizing real world relevance, cultivating reflection, and utilizing public presentations. Research-based pedagogies are made approachable for teachers and students in much the same way DIG Deeper elevates the three teaching practices: Debate, Illustrate, Generate.

The concepts behind OKC Equip and DIG Deeper are synergistic and expand collaboration by naming the essence of each teaching practice and branding them in ways students and teachers can understand, personally connect with, and easily discuss. Naming and branding pedagogies in this way expands collaboration and shifts schools and classrooms toward a culture of equity, leading to deeper learning.

Innovation and branding is not a new concept in education nor is deeper learning. But when new ways of thinking and teaching are branded, researchers, practitioners, and students, have a common space to buy in to the innovation, and this buy-in creates an open-source means for iteration and growth for each stakeholder. The implicit becomes explicit.

Branding innovative teaching ideas can also serve as motivation and drive to continue the work beyond the initial scope of the project. A succinct brand makes it easier to enlist others outside an RPP to share the work. If teachers believe that the practices have been of use to them, branding makes it easy for them to share that value with others.

We are so grateful for the opportunity to learn from BCPS and Outlier Research & Evaluation at UChicago STEM Education at the University of Chicago. This partnership continues to inform and inspire our work with Oklahoma City Public Schools.

There is a long-standing myth in education that goes something like this:

Whatever has been done before hasn’t worked. So, we need to come up with a new innovation that is based on high quality research. Then, we need to carefully design the innovation using all we know and test it out using very rigorous experimental or quasi-experimental designs. If we find that learners in the experimental group do better than their comparison counterparts, we will declare that our innovation is effective. And then, after communicating to the education community that our innovation is effective, people will do it.

This myth has been around in one form or another, for years. No doubt, basing innovation development on research is essential. Many have conducted diligent work to understand how people learn, the importance of critical thinking, and how to spark imagination and creativity. We need to capitalize on this and other knowledge to move forward in our mutual endeavor of improving education for all. But here’s the thing. We can’t cherry-pick the research we want to use and ignore the rest.

One area of essential research in particular, has been muffled: the long-standing body of work about change. This work is perhaps the most important in education. This is why: People don’t do things because they are effective. Effectiveness might make us consider doing something, but there is a vast space between considering and doing. And when it comes down to it, if people don’t do it, it’s actually not effective at all. Change isn’t that simple.

We already know an enormous amount about how to create, provide, facilitate, engage in and establish opportunities that will enable youth to learn. We have known many of these for decades. The problem is, people don’t do them. We can always use new ideas, but let’s not overlook the good ones we’ve already generated. Many of them worked in the ways we intended, they just weren’t used. Or if they were, they didn’t spread to others. And if they did, they didn’t last.

Over decades the field has tried to change systems, schools, administrators and teachers and yet, our challenges still persist. We have not succeeded in part because improving education is not about changing something or someone else, it is about changing ourselves. Change comes only from within; and it can be facilitated. If we are to make a difference, we need to find ways to help others believe in, know how to, and want to change themselves along with the rest of us.

Four years ago, through a research-practice partnership funded by the National Science Foundation, Outlier Research & Evaluation at the University of Chicago and Broward County Public Schools (BCPS) set out to find ways to find time in the elementary school day for computer science. We called the project “Time for CS.” In a strategy focused on using the time allotted for English Language Arts (ELA), we piloted and studied 6 interdisciplinary problem-based learning modules that included ELA, science, social studies and computer science. Over 100 3rd-5th grade teachers in eight BCPS schools used the modules.

The teachers were willing and even enthusiastic about using the modules. However, after trying them, they felt they didn’t have the time, resources and support to use the lessons as written. Typically, when they had to decide what to skip, they omitted the parts of the lessons that were designed to engage students in deeper learning practices. From the teachers’ perspective, the modules were “one more thing” added to their already-full plates.

This experience challenged our research-practice partnership to think differently about how to facilitate the spread of deeper learning practices in schools. When the Hewlett Foundation provided the opportunity, we took a different approach. We believe that the path to improvement is one of incremental, rather than sweeping changes in practice so instead of creating yet another complex reform, we focused on concrete, specific teaching practices.

We identified three teaching practices related to critical thinking that were common across subject areas and grade levels and that the teachers were already expected to use. They were: facilitation of argumentation (considering alternative points of view) facilitation of supporting statements with evidence, and facilitating communication (clearly articulated thoughts and ideas). We created an acronym for the practices: DIG, which stands for Debate (argumentation), Illustrate (provide evidence) and Generate (communication).

Our Hewlett-funded effort is called “DIG Deeper.” One part of our effort focuses on explicitly increasing teachers’ awareness of these practices while providing them with support for enacting these practices with greater frequency and quality. But change isn’t that simple. For change to spread and endure, we needed to do more than support the “what.” We need to support the “why.” DIG Deeper aims to build teachers’ will to use the practices by bringing about a shift in teachers’ mindsets about the role of deeper learning practices in their classrooms. The goal is to help teachers develop the intention and motivation to regularly improve their teaching practice.

Over the next year, we will be working with our “co-creation team” (a group of teachers and principals who are advising us) to grow that mindset shift across Broward County. In the coming year, together with our co-creation team, we plan to provide clear examples of the DIG practices, including demonstration schools and other champions who can show and talk about the tangible ways that the DIG practices support student learning. We will also provide tools, models and other supports that clearly illustrate how to DIG more deeply with students.

Teachers’ mindsets aren’t the only thing we hope to change. We are shifting our own mindsets as well. Having developed and implemented initiatives and programs in the past, we recognize that now, we are facilitating an “anti-initiative,” a reform that isn’t there. Teachers and students aren’t the only ones who need to DIG deeper.

In 2017, the Hewlett Foundation funded 10 Research-Practice Partnership teams, including ours (which includes researchers from Outlier Research & Evaluation at the University of Chicago and practitioners from Broward County Public Schools) to “develop empirically driven, practical approaches” to spreading deeper learning practices in ways that had equitable and sustained impact.

This is no small challenge, and it requires more than the work of only ten teams. This blog, Dandelionseedoutlier, is intended to be a place where the 10 teams and anybody else with something to contribute to our collective work can share their approaches, ideas, lessons learned, promising outcomes, frustrations, and illuminations. Posts may include but are not limited to: strategy descriptions, personal reflections, findings, new questions, challenges for discussion, resources, and invitations for collaboration. Together, we can make the progress that none of us can do alone.

To contribute, contact: dandelionseedoutlier@gmail.com.